Jersey &

Guernsey Law Review – February 2007

SHORTER ARTICLES

AND NOTES

A NOTE ON GUILLAUME

TERRIEN AND HIS WORK

Gordon Dawes

The Commentaries

1 In

1574 there appeared for the

first time Guillaume Terrien’s Commentaires

du Droict Civil tant public que privé,

observé au pays & Duché de Normandie. It is a

substantial work, covering some 765 pages of near foolscap-folio sized paper in

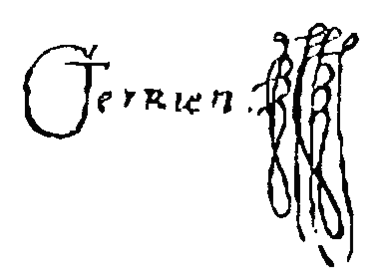

total, inclusive of indices. It

must have met with some success because it was re-printed in 1578 and then

again, intriguingly, in 1654, fully 71 years after the coutume upon which Terrien had been commenting

had itself been reformed comprehensively.

2 Terrien’s work has, of course, special significance

for the Channel Islands. Guernsey is particularly linked to Terrien via an

Order in Council of 1583 giving force of law to a document known as “L’Approbation”

prepared by the Bailiff and Jurats which literally

worked through the commentaries saying what was and was not good in Guernsey

law and how Guernsey law differed. Terrien

is also important for Jersey customary law without ever quite having been

elevated to the same status as an Order in Council, even if only by proxy and

only in part.

Little known facts

3 There

are many interesting facts about Terrien’s work

which deserve to be more widely known, although admittedly the audience for his

work is somewhat limited in this day and age. For example, each of the three impressions

(or editions; they are not really new editions

as we would understand the word) is very slightly different, not in substance

but in form. There are subtle

typesetting changes ranging from artwork to how words are abbreviated to where

lines break and so on. The page

references remain the same and nothing truly important changes; but it begs the

question why the book should have been re-set three times, perhaps

the blocks simply did not survive, which would seem odd for the second edition

at least.

4 There

were two authors of Terrien. I can sense the shock as I type those

words; although again I doubt that it is going to make the headlines, not even

locally. Terrien’s

own work comprised the selecting of texts from the Grand Coutumier, putting them into an

order which suited his scheme (even to the point of cutting and pasting quite

disparate texts) and then commenting on the resulting amalgam. To this commentary a further author

added notes headed “Additio”, more often than not in Latin. The precise identity of this later

author or editor is unknown.

Sources

5 The

range of Terrien’s sources is also extremely

broad, spanning the Old and New Testaments, Royal Ordinances, Roman jurists,

Roman law, contemporary legal authors, contemporary lawyers, judgments of the

Court of Exchequer and, of course, the 13th century Grand coutumier

itself. All are treated as

authoritative sources, with the result that Guernsey

and Jersey customary law are also indirectly

suffused with the same multiple sources, whether pre- or post-dating 1204 and the initial separation of the Islands

from continental Normandy. It is clear that the political

separation of 1204 did not entail fundamental cultural separation, law being a

lasting and tangible proof of this statement.

Reformed customary law

6 It

seems a fair assumption to make that Terrien’s

work would have had a profound influence on the redactors of the Coutume reformée

working in the years following the publication of his work. His work is also regularly cited by later

commentators of the reformed customary law. Terrien

remained an authority in continental Normandy

until the end of continental Norman customary law itself.

7 Apart

from the purely provincial, Terrien’s publisher, Jaques (sic) du Puys, considered the work to be of general usefulness

throughout the kingdom. He was

ambitious and enthusiastic for Terrien’s

work. The title-page included the

sub-title:

“Très necessaires

& requis non seulement aux Iuges, Iuriconsultes & Practiciens dudict Duché, ainsi

aussi à tous ceux des autres provinces & ressorts de ce Royaume”.

8 This

again suggests either an intended or perceived desire to address not just Norman customary law exclusively. It may be that Terrien

was concerned only with “Norman” law in its widest sense (i.e. not purely customary) and that du Puys saw an opportunity to promote the book as being useful

throughout the kingdom.

Terrien

the man

9 My

principal purpose in this note, however, is to say something of the man

himself, Guillaume Terrien. Unlike a later figure such as, say, Pothier we know comparatively little about Terrien. At the most basic of levels his name is

a French word. As an adjective it

would denote “terrestrial” (terrien) as opposed to “celestial” (céleste). As a noun it would signify a

landowner. Nicot’s

Thresor de la langue française

of 1606 illustrates the use of the word terrien as follows:

“Un homme

qui est grand terrien (sic),

qui a plusieurs terres et

possessions”. The first

edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie

française (1694) defines terrien as -

“Qui possede

beaucoup de terres, qui est Seigneur de plusieurs terres. Il n'a guere

d'usage que dans cette phrase. Grand

terrien.

Ce Prince est un grand terrien,

un des plus grands terriens

du monde.”

10 It

may perhaps seem rather naïve to adopt the literal definition of a surname

as saying something about its owner; but when one is considering the 16th

century the exercise has a little more meaning. In fact it seems

likely that Terrien did come from a reasonably substantial

family judging by the material available to us. First there is the evidence contained

within the Commentaires

themselves. The title-page tells us

(and there is no reason to doubt) that he was Lieutenant General of the Bailiwick of Dieppe, in other words a

reasonably senior figure in the administration of that district. He had died prior to the date of the

first publication of the Commentaires

in 1574. Jacques du Puys tells the story of the work in his dedication to Jaques de Bauquemare, Seigneur of Bourdeny, Chevalier,

Privy Councillor and First President of the Court of the Parlement

of Rouen. It was the heirs of Terrien who had sent the text to du Puys. Terrien had

written or concluded the work shortly before his death. It was du Puys

who (not being a lawyer himself) had sought the opinion of experts who

commended the work to him - with the result that it was published without

further ado or delay.

Le Verdier’s paper

11 Monsieur P Le Verdier, Docteur en Droit,

Président de la Société de l’Histoire de Normandie, wrote a paper for a Semaine de

Droit Normand held in June 1929 entitled

Quelques notes biographiques sur Guillaume Terrien.

It seems that M. Le Verdier

had made a detailed study of such public records as survived and concluded that

he was born at some time between 1510 and 1520. Le Verdier

places his death in either 1573 or 1574.

It appears that he was certainly still alive in 1573 from records

concerning the Rouen Cathedral Chapter.

Le Verdier suggests that he died only a matter

of months before publication of the Commentaires but

that -

“Ce

livre, si considérable et d’une si haute érudition, ne peut

être que l’œuvre d’un grand nombre d’années

…”

Which translates as follows -

“This

book, so considerable and of such high erudition, could only have been the work

of a great number of years …”

12 This

seems a fair inference from the 765 pages of the text itself; although it is

followed by the speculation that he died not very old, which itself depends

upon his rather speculative dating of Terrien’s

birth. Le Verdier

also deduced from various documents that Terrien was

married to a woman called Huguette and buried “devant la Vierge, en l’église de Saint-Rémy”,

i.e. before the Virgin in the church

of Saint-Rémy. No inscription had

survived, however, even as at 1929, when Le Verdier

was writing.

13 Terrien was both an advocate and a magistrate. Le Verdier

found references to Terrien in documents from the

1560s. He appears to have been

retained in some way by the Rouen Cathedral Chapter. Indeed the Archbishop of Rouen was the

temporal lord of the town of Rouen,

and it seems that Terrien’s office as Lieutenant Général

was a seigneurial office. An earlier judicial office was also

linked to the Chapter and seems to have been inherited from a Jean Terrien, most likely Guillaume’s father. Indeed there was an earlier Guillaume Terrien, active in the second half of the 15th

century, who is likely to have been Terrien’s

grandfather. There is evidence for

a later Guillaume Terrien, possibly a grandson. In any event it seems that our Guillaume

Terrien was a member of a legal family.

14 Perhaps

most exciting of all is the fact that Le Verdier

includes a facsimile of Guillaume Terrien’s

signature as found on documents dated 1549 and 1560.

Fig. Terrien’s signature, as it appears in Le Verdier’s paper.

The intertwining of the G and the T into

a single initial letter is striking; as is the elaborate conclusion. Le Verdier is

quick to concede the relative poverty of his research, but it is a great deal

better than the little or nothing which the Commentaires tell us.

Terrien

online

15 It

is a remarkable and wonderful thing that the four Channel Island jurisdictions

of Alderney, Guernsey, Jersey and Sark should still treat as authoritative a

work first published 433 years ago; a work which was itself commenting (at

least in part) on law first collated some 330 years or more before even that

time. The use of his work is a

hallmark of Channel

Island law, a

distinguishing feature to be treasured as contributing to the identity of the

Bailiwicks.

16 It

is therefore appropriate and very much to be welcomed, that the Jersey Legal

Information Board has made a photographic copy of Terrien’s

text available freely online at http://www.jerseylaw.je/publications/library/pages/terrien/default.aspx

together with a transcription of the table of contents. It would be wonderful to bring Terrien back to life in order to show him the enduring

nature of his achievement and how his work can now be viewed in every corner of

the globe where there is a computer linked to the internet. He would surely be amazed and

delighted. I wonder what he would

have made of modern law and, in particular, its quantity, complexity and

relative inaccessibility to the ordinary person (any person quite frankly). Not very much I suspect.

Gordon Dawes is an

advocate and partner of Ozannes, Guernsey, and author

of Laws of Guernsey, (Hart Publishing 2003). He is also responsible for the

forthcoming publication of a facsimile of the 1574 edition of Commentaires du Droict Civil tant public que privé, observé au

pays & Duché de Normandie,

par Maistre Guillaume Terrien,

together with new introductory materials,

from which the above article is derived